In 1941, Allied forces invaded Italian-held

east-African territories to ensure the security of the British communications

and supply lines between Egypt and the Empire’s possessions in the Indian Ocean.

A swift resolution to the action was crucial to allow the Allied troops

involved to reinforce their comrades in the North African theatre. This is the

background of Kim Kanger’s latest offering, La Primogenita (Legion Wargames,

2022).

La Primogenita is a redevelopment of Kanger’s

earlier game, The Road to Cheren (Revolution Games, 2013), which used a chit-pull

order activation system. The game was received favourably, if the comments on

BoardGameGeek are anything to go by. La Primogenita retains most of the

elements of the original game (force structure, map style, but expands the

parameters of the map, and replaces the chit-pull orders system with a new order-selection

system (more on that later).

Appearence

La Primogenita comes in a sturdy, lightweight

box with evocative cover-art featuring aa famous propaganda poster from the region

(featuring the slogan, Rìtorneremo! – “We will return!”). As mentioned,

the map is very close in appearance to that of the Road to Cheren, but has been

increased in size from the standard 17”x22” to 22”x25 ½”

(six-panel folded). The terrain elevation runs from Flat, through Rough and

Mountain, to Alpine. The colour pallet reflects the harsh environment, and the

incorporation of elevation markings help to convey to the players the sheer

scale of the undulating countryside in this part of the world (with some

points reaching over one and a half miles vertically). Rivers are marked, but

don’t affect movement as the country had been experiencing drought conditions for

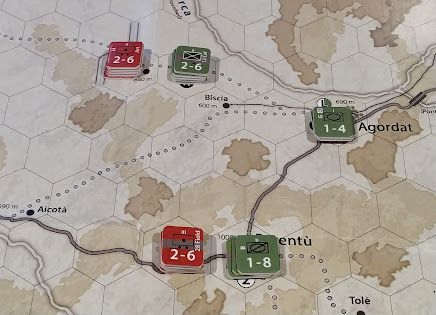

several years before the outbreak of hostilities. The counters a clearly visible

on the map-sheet, although it has been argued that the combination of primarily red

and green units in wargames can be a hinderance to some players with colour-blindness.

|

| Setting up for a solo game |

The playing pieces are simple and

effective, using NATO icons for the unit type, with the other information

clearly visible (I was able to read the counters without resorting to reading

glasses). The rules are also clearly printed and well laid-out, with particular

attention given to the innovative order mechanism. It would be churlish to

complain about a lack of index; I really didn’t experience any problems finding

what I needed to when consulting the sixteen-page rulebook.

Also included are two orders charts,

one for each player to lay out their orders selection, and two bi-fold orders

explanation player-aids, which can helpfully double as shields when secretly selecting

your orders.

Play

While La Primogenita is a relatively straight-forward wargame,

it is a showcase for Kanger’s novel order allocation system, which replaces The

Road to Cheren’s order chit-pull mechanic. Each side has a set of order chits displayed

on a board in three sets; Main Orders, Minor Orders and Combination orders that

work in conjunction with specific Main orders. During each turn, after

housekeeping and supply-check phases, the players – in secret – choose four

orders to execute in that phase. The orders are numbered variously through the two

sets, and when revealed, these orders are laid out on the Order Track in their

numerical order, from highest to lowest, with each order being returned,

face-down, to its position on the order table. The orders are then executed in

that order. After the option of some rail movement for the Italian player, a

second round of orders are chosen. Some previously used orders (back-printed) may

be reused in this round, but at the cost of a second order-slot.

|

| The Order Track, with selected orders in numerical order (Arial bombardment always comes first) |

Main orders generally apply to all units, while Minor

orders usually apply to a single unit. Up to three Combination orders can be

selected and held for use in conjunction with a sympathetic Main order.

The rules for supply reflect the difficult terrain

that the action was fought over. Units must remain withing eight Movement

Points of a supply depot. There are placeable supply points for the Allies, but

these are limited in how many units they can support at full strength. When the

last order for the second round is executed, Emergency Reinforcements

(placement of any reinforcements due that turn not already delivered by an order)

are placed in their appropriate places with a disrupted marker, a resupply

check is made of all units (with any out-of-supply units marked with a Low-Supply

marker), Units completely out of supply are removed, and a points-check is made

for sudden death victory conditions. If the Allies reach 20 points, they

automatically win; if, after the sixth turn they fall below 7 points, a

well-deserved automatic win is given to the Italian player.

|

| Casualties taken on both sides |

Appraisal

Kim Kanger is, for my money, one of the most

innovative game designers working today. He focuses on conflicts that have been largely

ignored by the broader wargaming community, like this small forgotten chapter in a much

larger theatre of war. The order-bidding

system in La Primogenita is revolutionary. It’s not something that would be

appropriate to just any situation, but it was literally made for this historical

moment. When I unpacked the game and began to read through the rules, I

wondered if I’d easily get my head around the orders selection mechanics, let alone

be able to instruct new players in it. My first game was a two-handed solo play-through,

and while I struggled in the first round and made a few mistakes in the second

(like completely ignoring the combination orders for both sides), by the fourth

round the order selection and play had become second-nature. I found it remarkably

intuitive after I’d gone through the process a half-dozen times.

With their superior armour, mobility, and air-support, one could be forgiven for assuming – all things being equal – that the Allied player should win handily at least 70% of the time. But time is against the British, and a competent denial-of-progress defence by the Italian side, utilising the natural limitations of the terrain on stacking and movement, can slow the advance of the Allies and put the defenders on a more equal footing. La Primogenita is a remarkably well-balanced game that defies assumptions and offers many, often torturous, decision-points in every round of play.

La Primogenita is no one-trick pony. This is a game

that richly rewards repeated play. It is a gem of a game that won’t outstay its

welcome in any hurry.