Unboxing

posts are usually reserved for new games. Some people see them as a waste of effort

or worse, free advertising. I’ve always been grateful for unboxing videos when

I’m thinking about buying a game – call it doing due diligence – and that’s

what I try to do with these posts. So, while this isn’t a new game, but it’s

new to me, it’s unplayed, something of a minor classic, and I think it warrants

consideration.

Wellington: The Peninsular War, 1812-1814 (GMT Games,

2005) was a follow-up to designer Mark McLaughlin’s Napoleonic Wars (GMT

Games, 2002), which covered the period from 1805-1815. At the time of its

release, Wellington was seen as something of a stripped-down version of

Napoleonic Wars; less scope, shorter duration, reduced players, simpler diplomatic

sequence. But this prejudice reeks of the difficult is better approach to wargame

design that permeated some quarters in the nineties and to a degree, still shows

up today. Here at A Fast Game, we’re all for a little streamlining and

simplification in our games if it doesn’t take away from verisimilitude or player

agency.

I

scored my copy of Wellington from another wargamer in my town who needed to

thin the herd. Imagine my surprise when I opened the box and saw the game hadn’t

been punched; only one of the two card decks had been reed from its cellophane

enclosure. This got me to wondering about why people acquire games only to have

them take up valuable real estate on their shelves, but that is probably a

subject for another post.

The box cover is a classic Rodger B. MacGowan piece, evoking the sieges, harsh conditions and hard fighting that characterised the struggle against Napoleon’s forces in the Iberian Peninsula. The illustration highlights the game’s namesake with a portrait of the young Wellesley in dress uniform, flanked by the Duke in his habitual black coat.

GMT

boxes from this time were solidly-enough constructed but the cardstock used was

a little lighter than what it used now, and with repeated removal the lid would

develop a slight camber to the long outside edge panels (I don’t want to

suggest this was exclusive to GMT – I have several older games that exhibit the

same kind of bulge). This actually makes it easier to get the lid off, even if

it is a little unsightly (but if that’s the worst that happens, it’s too small a

thing to be irritated by).

The lower half of the box had kept its shape admirably. From the box back, we learn that the game is a CDG with a point-to-point movement map covering Spain, Portugal and southern France, that it is a game for two to four players, a unit Strength Point represents roughly 5,000 men, and each turn covers one year. This is something that’s always bugged me in the conventions of conveying wargame information, that sometimes “Time” is used as the period covered by a single turn, and sometime (less often) as an approximate or expected duration for a game. The only company these days that I know of that presents this consistently is Worthington, with their “Victory within # hours”, and that’s a relatively recent innovation. I solely wish more companies would follow suit, But I digress. The Game’s complexity is rated at four out of nine, with a solitaire suitability of only two out of nine. I do appreciate the consistency with which GMT has adhered to their nine-point complexity/solitaire-suitability scale, though I have occasionally had cause to question its accuracy, but that probably has more to do with my comprehension skills than the scale itself.

The

back cover also provides some samples of the cards from the game, as well as a

representation of the playing pieces. The game uses a mix of round, square and

hexagonal counters representing troops, garrisons, and other game functions, as

well as markers for various game conditions, and tall, rectangular counters

designed to be held upright by plastic standees. The game wears it’s DNA on its

sleeve; appearance of the playing pieces and the cards – and to a lesser degree

the map – betray a heritage running back to the first card-driven game, We the People (Avalon Hill, 1993) (which designer Mark Herman later reworked

into Washingtons War (GMT Games, 2010)).

The Wellington rule book comes in at 24 pages, but discounting the cover page, Table of Contents, prefatory note, glossary, and an abbreviated Sequence of play on the back cover, the actual meat of the rules comes to just eighteen pages. It is black & white throughout and printed on a very sturdy-feeling matt paper-stock.

|

| Rule book - sample page. |

I haven’t gone through the rules in too through a manner, but a cursory look suggests that they are straight-forward and functional and shouldn’t be too difficult to interrogate and interpret at the table. From what I have read of the rules, I’d concur with the difficulty-4 rating.

|

| Wellington Play Book, with Mr MacGowan's nod to Goya on the cover. |

Part Two is an example of play, which is always welcome. Part Three covers the historical background (including a one-page survey of the belligerents and their leaders), player’s and designer’s notes, while Part Four offers a functional breakdown and explanation of each of the cards in the Event Card deck.

|

| The back cover of the Play Book has the set-up guide for the 1812 start. Inside the back cover has the set-up for the 1813 game. |

The last two pages feature set-up guides for the two play options; As the title suggests, the game begins in 1812, when the conflict historically reached a level of consistency of kinetic action over the campaigning months, or you can begin in 1813 for a shorter game.

|

| Cartes de quartier general pour le Armée de nord, et le Armée de sud. |

|

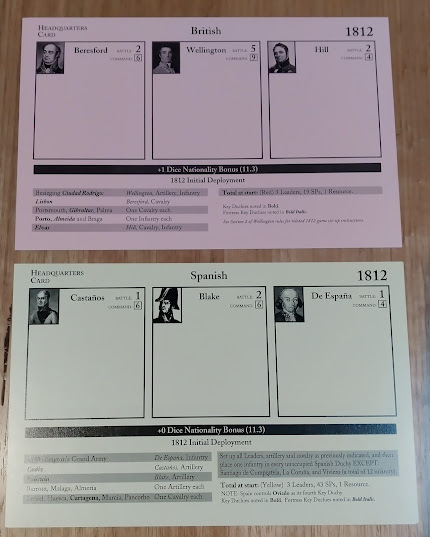

| Headquarters Cards for the the British and Spanish factions. |

Included in the complement are four Headquarters Cards, one for each faction. These are double-sided for either the 1812 or 1813 set-up, and they include instructions for initial placement f forces, as well as a box for the troops attached to that faction’ three leaders. This will board-clutter and add some mystery to encounter battles, as you’ll never be completely certain what the enemy you face can bring to the fore until you engage with them.

|

| The battleground. |

The map is typical for this type of CDG. Manoeuvre is regulated by point-to-point movement. Different types of connections may impose various restrictions on an formation: Clear roads are, of course, the easiest to traverse; Rough roads don’t add a penalty to movement, but do make it harder to Intercept of evade an enemy force; a Pass through the mountains will potentially inflict attrition on the travellers, while on a path crossing a River, the formation will not be able to Evade an enemy force and may take further attrition if retreating over the river.

The map

itself is printed on paper with many of the charts and tracks necessary for

play made available, along with a map key, movement reference tables (two, each

facing a long edge of the map) and spaces marked out for the card draw-deck and

discards, as well as Reserve cards each for the British and Spanish, and a

shared space for the French factions.

The game’s single Players’ Aid Card offers several less often used tables and guidelines (the interception/Evasion Table and Battlefield Loot Table (to the victor go the spoils), and instructions for the allies’ attempts to garner reinforcements, ‘Letter to the Horse Guards” and “Levantamiento Popular”), and copies of the Line of March Effects and Appeal to the Emperor charts that appear on the map. The PAC also includes two tracks; the Control Chart keeping a record of how many Duchies are under the control of a given faction, and the Casualty Display. I haven’t got this far in the rules, but while the Casualty Display is probably only used in combat situations, I would have thought the Control Chart would be a persistent record that would have been better shoehorned onto the map somewhere rather than on a card meant to be shared. But this is only a minor gripe on my part, and I probably should investigate the rulebook further regarding control before casting aspersions on the design.

|

| Counters enough for all your Imperial exploits. |

Wellington

comes with three counter sheets, all irregular in format, given the game’s

compliment of round, hexagonal and rectangular markers. The counters are

printed on fairly thick white-core cardstock, with good registration on each

sheet.

The

sheer variety of components is worth noting, although as I mentioned earlier, to

anyone with experience with this style of CDG, most of these should be

familiar. Flag markers indicate a nation’s control of a duchy, which could

change hands several times over the course of a game. Units are simply a

reflection of strength, and can be “made change” when necessary, swapping out a

4-strength token for a 2-strength and a couple of 1s. Some markers denote

in-game conditions, such as a siege that requires resolution. But one of the

most interesting (though again, not unique) counters are the Leader counters. These

are designed to stand upright in plastic standees (also included in the game).

As

usual, the artwork is historically representative and really quite nice.

Wellington will look good on the table.

The game comes with two decks of cards, 110 in all. These are divided into Home Cards (short decks specific to the factions) and what the rules refer to a “other cards,” but for clarity I’ll refer to as Event Card. The Event Cards make up the bulk of a player’s hand and bring an element of randomness to the game. Anyone who has played a CDG will be familiar with how these work, but for the uninitiated, most cards will give the layer the option of playing the card either for its Ops Value – the number printed in the top-left corner of the card, allowing you to conduct operations to the value of that number or less – or for the event described on the card. Some cards are mandatory events (with no Ops value) that you will have to play, even if the event puts your or your ally’s faction at a disadvantage. What can I say, war is hell.

|

| Home cards. always welcome. |

Each faction has its own Home Cards (the Frech factions share a larger deck). Each hand you’ll draw two of these (three if you’re British) along with six Event Cards. Unlike the random nature of the Event cards, the Home Cards always offer positive benefits for the faction, and sometimes that benefit will persist throughout the current round. An appropriately-timed Home Card effect could turn the tide for a game not going the faction’s way. These cards can also, of course, can also be used for their Ops value.

Wellington comes with eight dice (a little smaller than the dice you usually find in a GMT game these days, but they are in a really lovely dark Uniform blue with burnished gold pips like little brass buttons – very thematic – and a bag of black plastic standees (I’ve heard some refer to them as mounts, but that should, I think , be reserved for horses) for the General/Marshal counters. I’m not a huge fan of miniatures in board games, but I really like these standing figure flats representing the force under their command. I never said it was logical.

So that’s

my survey of Wellington. I kind of bought this on spec, not knowing when I’d

get around to playing it, but having had a good look through it now, I’m kind

of keen to get it to the table. Probably solo to begin with, until I’m confident

I’m across all the moving parts, but at first blush it seems like a very

playable game with built-in constraints.

Before I finish this off, I just wanted to share two more pieces I found in my copy of Wellington, artifacts of a bygone time which it's previous owner had not seen fit to part with, and I find myself similarly disinclined. The first is an advertisement sheet for some of the other titles that were new to the GMT catalogue when Wellington was released.

|

| EotS, Under the Lily Banners, AND Men of Iron. What a time to be alive. |

|

| Thank you, Cha. |

No comments:

Post a Comment