Computer kaput.

Never again, Lenovo;

In HP we trust.

If board games are prisons, then the best ones offer mild sentences. - Ian Bogost

I had to run some errands today, but I managed to do something I’ve been meaning to since it arrived in May; I finally got Task Force: Carrier Battles in the Pacific (Vuca Simulations, 2023) to the table. If you’d like a better look at the whole game, Task Force was the first game I “stripped down for parts,” and my effusive commentary and component photos of questionable quality can be found here.

The first

three scenarios are single-player tutorials, introducing the concepts and rules

gradually. I’m somewhat a novice when it comes to modern-era naval games so I

appreciate the approach. There are some excellent materials available on

YouTube; Ruff at Rough Swordsman and Michael at Boardgames Chronicle both have

good playthrough videos, and I’m not embarrassed to say I’ve been checking both

out. Thanks, fellas.

|

| Helpful scenario set-up board, populated, |

The first

scenario is the Attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). The

intention is to introduce how the air-to-surface combat and air-defence rules

work (a crucial part of carrier operations), before moving on fleet movement

and conducting search operations. I always appreciate the opportunity to learn

new games with unusual concepts or mechanics in bite-sized chunks rather than

the sink-or-swim approach. I’m not saying it’s the best way to teach and learn,

but it works for me.

The set-up

took a little longer than it might have if I’d used counter trays; there is so

much in the box that there was no way the three GMT trays I’d need to

accommodate everything were going to go in it (one would have been snug). I

bagged up the ships for each side by class, except for the carriers, which each

got their own bag to accommodate their air assets. While some of the planes

were generic land-base planes, three-quarters of them were from the carriers

involved in the actual Pearl Harbor raid, so I had to go fishing through extra

zip-loc baggies to make up their numbers.

Once the

helpful scenario template was filled, setting up the game map was a simple task

and quickly done. The Scenario 1 map is printed on paper; it’s the only one in

the whole box not mounted, I’m guessing because the scenario was written

specifically as a teaching exercise, and not meant to be repeated more than a

time or two.

Initial set-up (the calm before the storm).

The attacking

IJN planes are a mixture of high-altitude bombers (B), dive-bombers (D) and

modified Torpedo bombers (T). To make it a bit more of a challenge each wave completely,

then rolled, so as not to be able to cherry-pick weakened targets. Well, that’s

not entirely true; the scenario rules allow the first four planes attacking to

strike without dealing with AA fire from their targets. These were straight

runs, so I set these up first. I went straight for Battleship Row, and the two

closest to the mouth of the harbour channel, the USS Oklahoma and USS West

Virginia. I paired a much weaker B-Kate unit with a T-Kate unit from Yamamoto’s

flagship, the Akagi. The West Virginia got a full-strength unit of T-Kates from

the Akagi and the half-strength T-Kate unit from the Kaga.

Remainder of the First Wave; they'll have to deal with AA fire.

In

air-to-surface combat in Task Force, a low roll is a good roll. The attacker

also gains a -2 modifier when the target is stationery (e.g., a land-base or a

docked ship). Reader, I rolled ones on the Air-to-Surface Chart, sending the Oklahoma

to the bottom of the harbour and falling just one point of damage short of

sinking the West Virginia as well. Big ship damage is handled quite well in

Task Force. A battleship can shake off repeated hits of a few points (it’s a

battleship, after all), but each one has a rating on the lower left corner,

usually a 7 or higher. Let’s talk about the Oklahoma (7-rating). Meet or exceed

that number in a single attack, and that puts a Minor Damage marker on the

ship. But it doesn’t stop there; one more point of damage takes that marker off

and flips the counter to its Reduced side. The Oklahoma has a 7 on this side as

well. If the result you rolled was ten (7 + 1 + 2), it would end there; the big

old battleship would shake off those last few points. If the result was a

fifteen though (7 + 1 + 7), that would tear through that extra seven points

and put a Critical Damage marker on the ship. A critically damaged ship can’t

manoeuvre or defend itself, and just one more point of damage will end it. The Kates

hit the Oklahoma for nineteen points.

The USS Arizona sustaining damage.

The West

Virginia was a younger ship, and structural improvements had been incorporated from

the laying of her keel. Her initial integrity factor was 9, with another 7 on

her reverse side. Her initial attack fell just one point short of sinking her

outright.

|

| The Second Wave attacks. |

I could go

and on with stories of the glory my brave pilots brought to the Emperor, and of

the sheer tonnage of metal sent to the bottom of Oahu harbour, but suffice it

to say five ships were sunk, four battleships

(the West Virginia among them) and the light cruiser Honolulu with another two

battleships damaged (the Arizona significantly, the Maryland only lightly –

probably operational again within days) and a cruiser, the San Francisco, for a

total of 30 scenario points, a full battleship short of the prize. To “win” the

scenario, 35 points would be required to reach a major tactical victory, 40 for

a decisive tactical victory.

The USS Maryland, takes 9 points damage; one more would have flipped her.

I could run

though it again, see if I can sink even more ships, but I don’t think so. This

was meant to be a learning scenario, and I think I’d like to take the lessons

and move on to Scenario 2: Sinking off the Prince of Wales and the Repulse.

So, my 6x6 project

has taken another hit of late. My wife’s mother was in hospital for a time, and

has now changed her living arrangements. This has entailed a lot of people

(immediate family, including yours truly) putting a lot of time and effort into

ensuring as smooth a transition into this situational change as possible. This is

the primary reason for the dearth of blog-posts from this end in the last week

and some. She's doing a lot better now, I'm happy to report.

Added to

this was T having to skip not one, but two Monday night games due to having just

got back from a work trip to Europe, only to leave in a day or so for the

States for another work-related conference. Good for the travel industry, but

bad for my diminishing chances of actually completing even four of the six

games I’d hoped to play six times each. I haven’t given up on this – I’m still

going to try to finish the Napoleon 1806 and Fire and Stone cycles, and I’ll

try to get at least another one to the table – but completing the challenge is

going to prove too, er, challenging.

Anyway, for

the first time in some weeks I have a relatively clear couple of days, and I

have rather decided to make the most of them; I have a lot of gams I’ve been

wanting to try out and my plan is to get at least one to the table every day

this week. The key word here is “try”. No promises, but the times I do manage

to get a game played, I’ll write something about it here. Don’t come looking

for in-depth analysis; after one game or a couple of tutorial scenarios, you’ll

just be getting my first impressions, but I’ll try to keep it interesting.

First cab

off the rank was Dawn’s Early Light: the War of 1812 (Compass Games,

2020). I’ve been fascinated by the War of 1812 since I read two books on the

subject, back-to-back. I’ve been eyeing off the game for about a year. I hadn’t

heard much in detail – most short reviews compare it favourably with For the People (GMT Games, 1998) and Washington’s War (GMT Games, 2010). What

tipped me toward buying it was the ratings on BoardGameGeek; I’m inclined to

take anything on BGG with a grain of salt, but of the folks who took the time

to rate Dawn’s Early Light, nearly three-quarters rated it an eight or higher

out of ten. So, I took the punt.

Dawn’s Early

Light is a card-driven game (CDG), that plays out in a similar fashion to other

CGDs, such as the aforementioned Washington’s War. The game is played out over

eight full turns, with a truncated Prelude turn. In the Prelude turn, the

twelve cards of the Prelude deck are dealt out to the play, who take turns,

Americans first, to play a card for the Ops points (from one to four per card)

or the Action. If the Action is solely usable by the other side, they will play

the action out, but the active player gets to decide if their antagonist does

their action before or after they’ve played their Ops-fed actions. So far, so

familiar. But the interesting stuff happens out of the gate. IN a regular turn,

each player will play through the eight cards in their hand. In the Prelude turn,

only four of the six held cards are played. The other two cards are retained as

the foundation of the players’ initial eight card hands, while the discarded

cards are shuffled right back into the 1812 deck. At the end of the fourth

round, the smaller 1814 deck is shuffled into the remaining draw deck, and play

continues until the last card of both player’s hands have been played.

There is

also a three-tier Social Discourse track, covering the Diplomatic and economic spheres of the conflict and the public opinion among the belligerents' civilian populations. working up the tracks offer some advantages through the course of the game. Various events allow you to increase your influence on one or more of the tracks, or to reduce the influence of your opponent.

Dawn’s Early

Light is a straight-up CDG. It walks, flies and quacks like a CDG. I that

sense, there aren’t any surprises here. What makes the game interesting is the

historical event it’s modelling. The War of 1812 – referred to at the time as

Mr Madison’s War – was a protracted period of hostilities that, for the most part,

was a fairly low-ley event compared to the continental conflicts of thirty

years prior and fifty years after, but when it ran hot, it did spectacularly so.

Land combat

is conducted simply and organically in Dawn’s Early Light, and is inevitably

the result of other actions. If you conduct a move action and your guys happen

to stop where the other player’s forces are already, they fight. The British

player can also prevail upon the Indians to conduct raids against American towns,

or simply to fight alongside their Regulars and militia.

Naval combat

on the high seas is abstracted to Blockade and Privateering actions, and

control of the St Lawrence River and the Great Lakes are reduced to a series of

control markers land combat resolution is a much simpler affair than in

Washington’s War. But the biggest shift from other comparable CDGs is the use

of area movement (similar to, of all things, COIN games, with regions and significant

cities). State boundaries are marked on the map (as are longitudinal and latitudinal

references on the map-edges, which I thought was a nice touch), but the areas

are defined by and large by the boundaries of the peoples native to the region.

This works well from a game-design point of view, while acknowledging the

prominent part the local Indians took in the ongoing hostilities between the Americans

and the British.

I like to

play a new game once of twice on my own before I try to introduce it to

somebody else, but I always struggle a little with CDGs. Part-way through this game

I realised I was playing quite cautiously. I wasn’t taking the kinds of bold

chances I might against another player. This didn’t prevent me from getting a

good feel for the game, but it did leave me wanting to have a go at it with a human

opponent.

So, there’s a snapshot of Dawn’s Early Light. I’ve only scratched the surface here. I’ll come back to this after I’ve played it a few times and write a full review. There’s a lot to unpack with this one.

This week T

asked if I minded meeting at his place for a game. We’ve both really been

enjoying burrowing into Napoleon 1806 (Shakos, 2917), but it takes a bit

of time to set up, with the two army boards, the pre-set block placement, and

such. So, I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to introduce my

partner in crime (crimes against rules as written sometimes) to the enigma that

is Fire and Stone: Siege of Vienna 1683 (Capstone Games, 2022). It’s my

most recent sub-in for my 6x6 list (if you missed it, you can catch the third

quarter progress report here). I’ve played it about four times now, but only

once with another person. The other times were learning games, and I don’t feel

like I’ve learnt much so far.

In case you

missed it, Fire and Stone came out last year, the first wargame release by

Capstone Games, a company best known for family games like Terra Mystica,

(Capstone Games, 2012), Orleans (Capstone, 2014), and Ark Nova

(Capstone, 2021). There is some debate over whether Fire and Stone should be

classified as a wargame; I try not to get in the middle of these sorts of

arguments, neither being an Owl or a Rooster, a Jet or a Shark, or whatever.

Granted, it’s unconventional; the game plays out on a hex-grid (tick for the

wargame camp), but said hex-grid is ten hexes long and only three columns wide.

It has wooden pieces for the fortifications and cannon, but the opposing armies

are asymmetric decks of cards. In this question, I’m going to defer to those

presumably more knowledgeable on these matters than me – the Charles S. Roberts

Awards board, which accepted a nomination for the game to be considered for the

Best Gunpowder Wargame category this year. It didn’t win, but it was in very

good company*.

Teaching a

game is good (with a forgiving audience) because it highlights any

misunderstandings you have or patches in the game that you’re not quite across.

There was a few of those in this game. But honestly, I was surprised I

remembered as much as I did of how the game plays. I don’t have enough

experience with the game to be able to say this with any authority, but I

suspect the Ottoman player has the ore straight-forward role in the game, that

of pushing ever forward and eventually controlling the Curtain Wall hex at the

Habsburg’s baseline, so I gave that faction to T to play. After going through

the turn structure and the options available – each layer deals themselves off

five Strategy cards, then take turns either playing a card for its event or

discarding a card to do an action – we got into it and learned by doing.

Fire and Stone looks like a difficult

game out of the box. The way it’s put together challenges your expectations of

what a wargame should be. But at its heart, it’s a game of simple parameters

but deep strategy. It’s actually rather easy to teach. Each of the five rounds

consist of five cards each, played consecutively, starting with the Ottomans.

You play a card for event or as an action, then your opponent does the same.

You have five tactics cards that give you a bit of a leg-up, but you can’t just

blow through them because you only have five of them for twenty-five (or

possibly more) event/action plays, and some of them might be reaction cards,

only playable on the other player’s action.

The game ran fairly smoothly for a

first go with a new player. T picked it up surprisingly quickly (more quickly

than I did on my first couple of two-handed solo forays). Like Worthington’s

Great Sieges games, if the last card is played and the Ottomans haven’t gained

control of the Curtain Wall hex, it’s a default win for the Habsburgs. This

wasn’t an issue for T; he laid his control marker on the Curtain Wall on the fifth

card of round four. I have to put it down to some luck, but mostly having the

nerve to commit his troops heavily to the battle actions that won him

successive hexes in the second and third rounds (this can be risky – commit your

best troops early and you run the risk of them being lost to enemy cannon fire

for the rest of the game).

This AAR feels a little shallow to me;

Fire and Stone is a nuanced game, and I’m still feeling out how everything

operates withing the game. But T’s game was like a bettering ram. That may have

come down to the card selection on the night. Nearly all of T’s card events

were aggressive ones. Mine tended to win back some troops of raise morale a

notch (I’ll talk more about morale in the next report). I’m not angry or

annoyed T won his first game. I’m just surprised at the sense of inevitability

it carried.

We’ll probably come back to Napoleon

1806 over the next couple of weeks, to draw a line under that, and get started

on the review (spoiler alert: it will be positive). But game three of Fire and

Stone won’t be too far away.

1565: Siege of Malta, Worthington Publishing, designer Maurice Suckling

Fire & Stone: Siege of Vienna 1683, Capstone Games, designer Robert DeLeskie

Nagashino 1575 & Shizugatake 1583, Serious Historical Games, designer Phillipe Hardy

WINNER: No Peace Without Honor, Compass Games, designer David Meyler

Wars of Religion, France 1562-1598, Fellowship of Simulations, designer Jerome Lefrancq

For our latest stab at Napoléon 1806 (Shakos, 2017), I took the lead of the French forces, giving T the Prussians to deal with. T won the initiative for the first turn (after we’d both drawn Rain events), and we got off to a soggy, exhausting start. A quick rules clarification; In our earliest games I’d misremembered the rule around rain; movement doesn’t cost an extra point, but every unit that tries to move – successfully or no – must take a point of exhaustion because, well, mud. And it rains so very much in the German countryside.

|

| Board state at the end of the second turn. |

Like I

said in the last report, both of us are becoming more aware of the

opportunities to use action cards, as T proved when Louis demolished a bridge

crucial to my right flank advance on his second activation for the first turn.

I’m beginning to regret teaching him this game.

Destroying a bridge doesn’t prevent your antagonist form crossing, but it does cost three movement points to get to get across the river at that point. Serendipitously, In the third turn I actually took out Louis’ column; the first casualty of the game, earning France points for the column reduced. Louis had stayed on the wrong side of the river, for reasons known only to himself. Ney, joined by Augereau, who was escorting Napoleon joined the battle and Louis was quickly seen to.

|

| At the bottom of the fourth. |

By the

fourth turn, Soult was within striking distance of Leipzig, which was thinly defended,

but I was wary of sending him in to battle less a card for the moving battle, when

whoever was guarding Leipzig (Blücher, I suspected)

would be gaining a card for the citadel defence. The Prussian deck might be

weaker, but Soult had already accrued some exhaustion; a lucky draw with another

five or six exhaustion points could remove him from the game (and tip the Victory

Points scales in Prussia’s direction). At the beginning of turn 5, Wurtemberg can

reinforce either Leipzig or Halle, so T positioned him in Leipzig, guaranteeing

further difficulty in taking the citadel. But that was okay. I had no intention

of attacking either of the cities.

I’d

been manoeuvring Davout and Lannes toward the prize, Erfurt, from different directions.

Lannes came from the west; he was there mostly to counter any mad dashes from

that flank by Weimer and Ruchel, although T had decided to try to use this slightly

underweight force to drive on Bamberg. I’d left Murat and Bessières there to block

their way at Coburg, and had ordered Augereau back to secure Bamberg in the

unlikely event of a breakthrough.

|

| Converging on Erfurt. |

At the

end of turn five, I decided to let Davout rest, a single connection’s distance

from his target, clearing his accumulated exhaustion. He’s only gained three

orange drums in his push to Erfurt, but I wanted his to have every advantage in

the coming assault. I had also been bringing Ney accompanied by Napoleon; they

were now withing two locations of Davout, so I chose to wait for them to join

up in the next turn. It weas a risk, nut I felt confident in taking it. Leaving

nothing to chance, I brought Bernadotte, who had been threatening a move on

Halle, to within striking distance of Erfurt. It was too far for any of the

Prussians to try to intervene in that siege anyway, and if they had vacated the

city, Soult may have been able to take it unchallenged if he drew a five- or

six-point action card.

At the beginning of Turn 7, we drew and I retained the initiative. Then a couple of things happened. I ordered Bernadotte to make an initial assault on Erfurt. When you order a column in Napoleon 1806, you point to the column you are going to activate, declare your intention (without naming the unit), and then draw a card to see if you have the points to execute the order in full or only partially. I drew a two-point card, which in this case offered enough points to commit the order in full. Now, in the Prussian Action Deck, there is a card entitled Bernadotte. The Prussian player can play this card whenever a solitary column is ordered. If that column is Bernadotte, BErnadotte's movement is reduced by three MPs. T played the Bernadotte card, and Bernadotte retired for the remainder of the turn (and the game).

|

| Well played, sir; well played. |

T sent

his southern force into battle against my chaps at Coburg, but were seen off. The

difference in the damage inflicted by the two sides (2 points to 1- one point

difference) gave me another point toward victory; I was now only three points away

from taking the field.

I

ordered Davout (with Ney and Napoleon, who had joined the camp the previous turn)

to attack Erfurt, and drew a 3-point card – success! The game would have ended

had I drawn a 1. I also had an ace up my sleeve; I played a Reaction card,

which would allow Lannes – only one connection away from the site of the battle

– join in the fray. Unfortunately, T also had a card up his sleeve; Counter-Order

immediately negates the effect of any action card just played. Lannes never

received the orders, and had to sit this one out.

Even

without Lannes’s support, the day belonged to the French. T had managed to

reinforce Kalckreuth in Erfurt’s defence with Tauentzien in the sixth turn.

Between them they could muster four combat cards, plus an extra one for the

defence of a citadel. Soult brough three cards to the attack, Ney another two,

and Napoleon offered one extra, but I also lost one for the moving attack. When

revealed, my five cards yielded four hits and an epic nine fatigue points to

the Prussians puny one hit and four exhaustion points. The Erfurt and the game

went to the French.

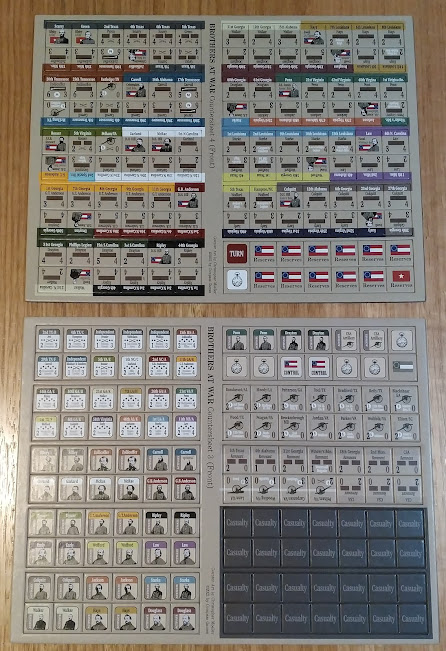

Charles S. Roberts Award nominee: Best American Civil War Wargame

Brothers at War, 1862 (Compass Games, 2022) is, as the name would suggest, an American Civil War game. And I can already hear people mumbling, “Hmmm, another ACW game.” If it’s not your thing, feel free to stop reading now. Brothers at War, 1862 is a regimental-level hex-and-counter wargame by journeyman game designer, Christopher Moeller. Moeller is responsible for the Napoleon's Eagles: Storm in the East (Compass Games, 2020) and the upcoming Napoleon’s Eagles 2: The Hundred Days (Compass Games, 2022) and the subject of Compass Games’s first “proper” Kickstarter campaign, the fantasy-themed wargame Burning Banners: Rage of the Witch Queen (Compass, 2024) which is slated.

Moeller has a day job as an artist for the Magic: the Gathering (Wizards of the Coast, 1993) behemoth. That’s all I’m going to say about that. I now realise that he was also the creator of the Iron Empires graphic novel series which I really enjoyed reading, and which got an RPG treatment in Burning Empires (Burning Wheel, 2006); and I'm now embarrassed that I hadn’t made the connection right off the bat.

Brothers at War, 1862 is a brigade command-level game, with a chit-pull activation mechanic. I'll cover that in the review. I’ve only come to chit-pull activation games in the last four or five years, but to my mind it makes for a much more dynamic game-play, especially for tactical games with an emphasis on manoeuvre. But I’m not here to discuss the design merits of the game; you’ll just have to come back for the review. Here I want to consider the apparatus of the game, the beauty and the magnitude of what comes in the box.

The box is of

2-inch depth and sturdy construction; Compass’s boxes – at least the ones I’ve

been acquiring lately, are generally pretty substantive and have a good fit

without becoming vacuum-seal tight.

I Like the

box-art for Brothers at War, 1862. It’s evocative while staying kind of

generic, which is fair, considering the geographical separation of the battles

covered in the game*. The game covers four battles from the Civil War –

Antietam, Fox’s Gap, Mill Springs and Valverde – and this is declared on the

right hand of the box-cover, which features a drop-banner showing portraits of commanders

crucial to the actions covered in Brothers at War, 1862.

The back of

the box conveys clearly the parameters of the game, declaring the scale; turns

are roughly twenty minutes long, the hexes are 100 yards across, the command-level

is brigade, but the pieces are regimental, so with each activation you’ll

likely be ordering two-to-four counters (again, putting an emphasis on manoeuvre).

The back also clarifies not only the four battles represented, but that there are

at least three scenarios to play for each battle (Antietam has four).

The box-back

also gives us a teaser of the map-art and the counters, with the representative

counters printed to their true size (¾-inch). We’ll circle back to these shortly.

Both the

Rulebook and the Scenario book are printed on nice, heavier weight gloss paper,

but not too shiny, so it’s eminently readable under lights. The rules for

Brothers at War, 1862 well-presented and very readable, with worthwhile illustrations

clearly spelling out perennially difficult issues for tactical games like line

of sight. I’ve read through the rules once – I like to give the rules a second

read before I try out a full scenario – and I didn’t hit any red-flag details. If

it’s presented clearly enough for me to understand out of the gate, then in my

opinion the designer, developer and any editorial folk involved have done an

outstanding job.

.jpg) |

| Rulebook sample page: Line of Sight examples. |

All five sheets

of counters printed on good grey-core stock and not too thick to fit into my

2mm radius Oregon Laminations clipper Four of the sheets are ¾-inch used for

units, brigade commanders, draw chits, off-board artillery tokens and other

sundry pieces. Before I go any further, I should point out that the placement

of the units in the sprues is an approximation of how they were printed. As I

carefully lifted out the first couple of counter-sheets, nearly all the middle

counter-strips fell out of the first two or three sheets. This isn’t a

criticism; they’re just very well-cut. I was surprised they’d managed to all

stay in place through the box’s various shipments. But when you come to unboxing

your own copy, don’t be too cavalier with the counter-sheets. You’ve been warned.

There is a fifth sheet of smaller (five-eighth, I think) markers which are all

so well cut, but not so that they fall out of their frame.

|

| Union forces |

The units

are clearly presented, and feature two states for the unit on the front and reverse

sides, rather than a step-loss. Infantry units are either formed or unformed;

cavalry either mounted or unmounted, and artillery batteries either limbered

(prepared for movement or unlimbered (battle-ready). The brigades are marked

clearly using a common colour bar across the brigade. The identifying colour

bar also appears on the battalion commander’s marker, and on the draw-chits used

in the activation of units in a turn.

CSA forces and other markers.

Smaller markers.

All in all,

the counters are gorgeous, and feel nice to play with. I’ve recently moved up

to working with a 3mm plexi sheet – something I never saw the need for until I

got it – and 25cm tweezers with a fairly broad gait, so it will be interesting to

see how well they accommodate the ¾” counters.

|

| Game maps for the four battle covered. |

The maps achieve a balance between

artistic merit and usability. To my mind are fairly utilitarian, but still

attractive to look at and play on, not at all stark or schematic. It’s my

understanding that Chris Moeller did all of the art for the project, including maps,

counters and play examples for the rulebook. The guy has some serious artistic

chops, but he also has the designer’s understanding of both what is necessary,

and what will work in a play surface.

|

| Antietam map. This map accommodates all four scenarios. |

I’m only featuring the Antietam map here;

I’ll show more detail pics when I get to reviewing the game, but for now you’ll

just have to take my word for it that they are all great. Elevations are shown

in a colour scale and kept to a manageable four. Elevation affects things like line

of sight and artillery deployment, so manageable is good. The way the maps have

been prepared betray an emphasis on playability, which I can’t fault. I’m eager

to start pushing around some counters. The hex-grid is a mere 14 by 20, with each

hex coming in at 1½ inches, side to side. Stacking rules in Brothers at War,

1862 are two units to a hex, but this way you don’t have to stack them; you can

have your units side-by-side, with all the important information available at a

glance.

.jpg) |

| Set-up guides for scenarios 1 and 2. |

The scenarios

are presented in four chapters, coinciding with the four battles covered in the

game. Each receives a brief introduction, along with some situation-specific

rules for that set of scenarios. The details for the units at play are collected

on the Scenario Charts for each side, for each battle. These will hep you track

the regiments within each brigade as well as the other ancillary units, like

independent cavalry, artillery batteries, and each brigade’s skirmishers. The

cards should remove the need for some of the marker clutter inevitable in this kind

of tactical game (I’ll look at this in more detail in my review).

|

| Activation tracking and Brigade management cards. |

|

| Player Aid Cards. |

Cards play a

big part in the game. Brothers at War, 1862 is a card assisted game; the cards

held by the player may, in a given situation let them shake off a disordered

penalty, or offer an extra dice in combat. Nothing game-breaking, but it makes

for a nice feeling when you’ve got the right card at the moment you need it. The

deck is used for all four games, so the there’s nothing too situation-specific.

The cards are of the standard I’ve come to expect from Compass Games; some might

argue they’re a little on the light side, but I personally don’t have a problem

with them. They are also nicely and simply illustrated, in keeping with the

overall feel of the game.

|

| Card samples. |

A handful of

cards are also used for managing the Off-Board Artillery. Some batteries are

located on the map – depending on the scenario – while others are held off-board.

The fact that they’re off-board doesn’t mean they’re immune to hostile fire;

that’s where the need for BBA management comes in. While I’m talking about

artillery, I want to mention something that I would normally leave for the

review, because it’s a mechanical point rather than a physical one. I just want

to note something because I think it’s neat. The range rating for the artillery

counters may seem a little short, usually # or so hexes. That’s the effective

range; long range for artillery is double the range stated on the counter, and

extreme range is triple. This is the first time I’ve come across this in a game,

so maybe someone else did it first, but this just seems an elegant way of managing

the potential difficulties of escalating ranges in tactical artillery.

Of course, it wouldn't be a Compass game without one erratum note

slipped in before shipping. This isn't a criticism.

By everything I’ve seen here, Brothers

at War, 1862 promises to be an excellent tactical simulation of four separate

and diverse situations that occurred during the second year of the American

Civil War. The observant reader may have noticed that I’ve persisted on using

the complete title – Brothers at War, 1862 – throughout this article. It’s my

understanding that Mr Moeller has stated his intention to make this into a

series of games, with new additions covering other years of the war (so he presumably

has at least two more in mind). I’ve used the complete epithet to, in my own small

way, encourage this endeavour. Based on this one, I’d really like to see, at

least, a Brothers at War, 1863 (BaW ’61 and ’64 would also be most

welcome).

This has been a by no means exhaustive look at what looks to be an entertaining and educating game; I jst wanted to share some of my excitement overt it. Brothers at War was one of my most anticipated games of 2022 even before it received a Charles S. Roberts Award nomination. I’m really looking froward to getting this to the table. I want to dive into this as quickly as I can and get a review out for you for your consideration. From everything I’ve seen – and read – of it so far, I’m left with little doubt that it will meet my expectations.

* The back box-cover noted that the

cover art is actually a nineteenth-century painting, The Battle of Antietam

by the Swedish-born American artist and illustrator, Thure de Thulstrup, which he completed

in 1887, 25 years after the actual battle.

Analysis paralysis. The struggle is real.

Tempus

fugit. We’re already

three-quarters through the year, which means it’s time for another quarterly

progress report. For those just tuning in, I started this blog as a tool to

keep myself honest regarding a gaming commitment I made to myself, to play six

games I’d owned for at least a year but hadn’t yet got to the table. This update

will look at what I’ve managed to play, what I still have to get played, what

changes I’ve made to the list, and what – if anything – I’ve learnt in the

process. This is the third quarterly report for they year; the two previous reports

can be found at: Report 1 (January-March); and Report 2 (April-June).

I ended the

second quarter on a sober but hopeful note. Most of my 6x6 games I end up playing

with my brother-in-law, T. He’s a good sport, always happy to try something

new, and once he’s grokked a new game, we tend to be fairly evenly matched. We

started meeting on Monday nights (sometimes Tuesdays) for a game when my wife

was in hospital for a couple of months in late 2010, and we’ve kept it up

since.

Sometimes T’s

job will take him out of town and we won’t get to game that week, occasionally

for two weeks of more. When that happens, I’ll sometimes be able to catch up with

B, the host of our Wednesday night game. This doesn’t happen as often as we’d

like due to clashing commitments, but we sometimes get to squeeze in an extra

session. Anyway, as it has transpired, the Monday – sometimes Tuesday – game is

where most of the 6x6 action happens.

.jpg)

Aces of Valor (Legion wargames, 2023).

Initially I

chose six games I’d been wanting to play for a while. I had a few ground rules,

not to make it more challenging for myself, but to make the experience more meaningful.

As I said previously, to start clearing my unplayed list, the games had to be

ones that I’d owned for at least a year, and I had to pick games to play

against another human being (no solitaire games, not that I had that many when

I started this, but it would have felt a bit cheaty not to have a flesh and

blood witness to the act). They had to be Wargames or war-adjacent games. I

decided not to duplicated publishers or designers, and while I didn’t spell it

out, I tried to pick games that seemed to have different approaches or design

philosophies. Each game I’d write a short AAR and after the sixth play, I’d

write a more in-depth review. The games I settled on at the beginning were (in event-chronological

order):

This War Without an Enemy (Nuts!, 2020)

French and Indian War, 1757-1759 (Worthington Publishing, 2020)

Napoleon 1806 (Shakos, 2017)

Great War Commander (Hexasim, 2018)

Churchill (GMT, 2015), and

Brief Border Wars (Compass Games, 2020)

Good list, I

thought. There was a couple of statistical artifacts that showed up when I

thought about it more deeply; the games were split evenly between American and

French publishers. At least three of the six were block games of one stripe or

another (a case could be made – from a purely component-based view – for a

fourth with Churchill). Overall, though, I was pretty happy with the line-up.

Within a

couple of weeks, the wheels started to come off. Churchill was the sticking

point. It’s a three-player game that can be played by two players with the aid

of a flowchart bot, but the intent of the designer was for it to be played as a

three-player game (like Triumph and Tragedy (GMT Games, 2015), another game

that really needs to be experienced with a full complement of players). And it became clear very quickly that it was going to be nearly impossible to corral another two players with any kind of regularity. It's hard enough getting one sometimes.

.jpg)

Undaunted: Normandy (Osprey Games, 2019).

After some

deliberation with myself, I settled on Undaunted: Normandy (Osprey

Games, 2019). This was a good choice – it was the same period as the game it

replaced – but it felt a little cheaty; I had owned it for the appropriate duration,

but I’d played Undaunted: North Africa (Osprey Games, 2020) a couple of

times (only ever solo, two-handed), and had enjoyed it so much I’d bought

Normandy on the strength of that experience, so it wasn’t like I was learning something

new from scratch. Still, While the fundamental mechanics were the same,

Normandy felt like a very different game in scope, intent and play.

My next line-up

problem came more recently when I started to look at This War Without an Enemy,

a game that simulates the situation of the English Civil War. Without question,

This War would have to be the most beautifully realised game in my collection. The

Terry Leeds map is worthy of hanging (I believe Alexander from The Player’s Aid

has a poster copy of it hanging in his gaming lair) and the block labels are exquisite.

Unfortunately, even the shorter scenarios will push out to three or four hours;

the set-up alone for my first test-run took nearly an hour, with checking, re-checking

and replacing some blocks for others (the title font is both small and in a

lovely but barely legible cursive script). I’m still mad-keen to get my teeth

into this game – it promises to be both a destination and a journey – but its

requirements prohibit it from 6x6 consideration.

The Barracks Emperors (GMT Games, 2023).

Which brings

me to my latest break from the stated guidelines I first set out, but it’s for a

good cause. Looking for a replacement for the This War Without an Enemy, I went

through my collection, hopeful of a game that stuck roughly to the chronology

of the original selection. The best fit was one I had actually played once this

year, but had only acquired this year, and that had been published just last year.

Fire and Stone: Siege of Vienna, 1683 (Capstone Games, 2022), is an intriguing

puzzle of a game. It’s played on a three-by-ten hex-grid, soldiers are

represented by a deck of cards, and the only game pieces are wooden cannon and

breastworks. While it doesn’t meet the one-year ownership requirement, Fire and

Stone more than makes up for this in the area of learning and mastering a

completely different kind of game.

I also had an

ulterior motive for adding this one. Half-way through the year, the Charles S. Roberts Awards for Excellence in Conflict Simulation for 2022 were

announced (a full list of the nominees and winners by category can be found here).

The CSR Awards are the wargaming industry’s earliest attempt to highlight and

celebrate the best of what your hobby has to offer. I’ve always taken a keen

interest in the awards, and I’ve been dismayed by the seeming lack of interest

across the hobby. I won’t go into any further detail here – I hope to put

something together about awards across the wargaming field sometime soon – but when

the CSR Awards were announced, I noticed that out of the roughly five dozen

games that were nominated, I already owned about fourteen of them, and had a

strong intention to purchase at least a half-dozen more. I’d already reviewed a

couple of the games, so I thought one way to highlight the CSRs would be to

review every game from the list that I could. I’ve been working through the ones

I already owned (at time permits) and have amended the reviews already

published with a note at the beginning of the review to declare the game a Charles

S. Roberts Award winner or nominee.

Plains Indian Wars (GMT Games, 2022).

It was for

this reason that I felt less remorse over the inclusion of Fire and Stone,

which received a nomination for Best Gunpowder Wargame. This will be a “two

birds / one stone” thing, some conservation of effort on my part. But the game

is also an excellent and frustratingly challenging game, in the tradition of

the best wargames.

Which brings

me to the current state of my 6x6 table. I’ll be honest, it’s looking a bit

dire. At the mid-way point I was somewhat hopeful of making up some of the lost

ground, but by the end of July I was coming to terms with the unlikelihood of

being able to meet the target of thirty-six games in total. And the start of

the year, thirty-six games in fifty-two weeks seemed eminently doable, but this

has been an eventful year. I don't think I will complete the task I set myself, and I'm okay with that. Well, I'm a little disappointed.

The project hasn’t been a wash, though. The reason I set myself a 6x6 challenge was to get some games off the shelf and onto the table, and it's done that. I fully intend to get as many 6x6 games in as I can in the last three months of the year.

I’ve also managed to play Commands and Colors: Ancients - Expansion 1: Greece and the Eastern Kingdoms (GMT Games, 2006). I couldn’t in good conscience shoe-horn this into the 6x6 list – I’ve played too many C&C games of all stripes to seriously consider this a new system to learn (although, as I’ve written previously, it’s a very different beast to out of the box C&C: Ancients), but it is nice to have finally gotten around to playing scenarios that have sat on my shelf for going on eight years or more (it's featured on the list as a reminder of the times we had to play at T's place for whatever reason and there wasn't time to setup one of my games – the nights weren't a total loss).

Keeping a

living journal of the games I’ve played has prompted me to play more games, and

to branch out into more solo games. I’ve played at least twenty-five games I

hadn’t played before since the beginning of the year. That count includes no

less than six solitaire games (several of which I’ve reviewed and posted on

this blog). That number includes three miniatures games that were new to me – one

WWII and two Napoleonic rules-sets – a couple of non-wargames (like the phenomenally

good Apocalypse Road (GMT Games, 2020), and a few games I’d describe as

war-adjacent, like Caesar! Seize Rome in 20 Minutes! (PSC, 2022 - which was nonetheless a Charles S. Roberts Award nominee for Best Ancients Wargame).

And I’ve had a ball playing nearly all of them (I’m not going to waste space on

the ones that left me cold; I’d rather talk about the worthwhile ones).

Fire and Stone: Siege of Vienna 1683 (Capstone Games, 2022)

Writing these pieces has also encouraged me to think more clearly and in greater depth about the

games I play, and to try to find ways to articulate all that thinking into

sentences that make sense. I’ve created something of a rod for my own back;

what started as a diary of game-play AARs has grown into something bigger. The

response to the reviews has been generally positive (no death threats yet).

People seem to like the AARs as well. I like writing these session reports

because they help me clarify my thinking around a game before I come to review

it. If you see some doubling-up of ideas, or me mentioning again things I may

have said already, this will be why. The AARs are like the early drafts; the

review is the more polished product.

I’ve got

some other ideas I’d like to explore, and some new things should be showing up

over the next few months. For non-6x6 game stuff, I’ll be spending most of my

time working through reviews for the Charles S. Roberts Awards nominee games,

but I’ll probably slip something else in from time to time as they come to hand

or as I get them to the table. If there’s anything in particular that you’d

like to see more (or less) of, let me know in the comments.

And, as

always, thanks for reading this far.

Dear readers, regulars, visitants, and fellow travellers. Once again, I have in my means a way to give back to the community. I’m happy ...