Worthington Publishing (and the company’s previous incarnation, Worthington Games) have a long and deep connection with the French and Indian War, as the North American theatre of the Seven-Years’ War (1754-1763) between the empires of Britain and France and their subjects and allies in the New World. Hold the Line (Worthington Games, 2008), and its revision, Hold the Line: the American Revolution (Worthington Publishing, 2016), each saw its own French and Indian War expansion (Worthington, 2008, 2016).

I was

on the fence about French and Indian War, 1757-1759 (Worthington, 2020) game when it was first announced. Because of financial

pressures at the time, I didn’t end up backing the Kickstarter; shipping to

Australia always add around half to two-thirds the cost of the pledge. I like a

block game, and I was thinking about grabbing a copy through Noble Knight, but

I already owned Volko Ruhnke’s classic, Wilderness War (GMT Games,

2001). With limited storage space and a lot of historical areas my smallish-but-respectable

collection doesn’t yet cover, could I justify buying a second French and Indian

War game.

What

convinced me was Bill Molyneaux’s review of the game on BoardGameGeek. Bill

designed the well-received Wilderness Empires (Worthington Publishing,

2015), as well as a sack-load of other games set around aspects of the conflict,

and is a historian and heavily involved in the F&IW re-enaction scene. He

said it was, to his mind, the best game covering the conflict (and mentioned

that his son prefers it to Bill’s own game). I confess, I haven’t played

Wilderness Empires, but Molyneaux is a consistently solid historical game

designer, so his endorsement counted for something with me. After reading his

thoughts in it, I pulled the trigger on French and Indian War.

Having

played it now half a dozen times and spent a lot more time thinking and writing

about it, I feel like I’m in a good position to talk about this game. Having

said that, I feel like it eludes me somewhat. It’s a simple game, very easy to

pick up. I’d say it’s an excellent game for introducing new players to wargaming,

and to block wargames in particular. But underneath its veneer of simplicity, there’s

an awful lot going on in this game, and I’m certain I won’t be able to cover it

all in this review.

Appearance

French and Indian War, 1757-1759 (F&IW) is

a spare game, the mounted board is a narrow, four panel item (11” x 32”), representing the region

in which the bulk of the action in the conflict took place from the

northern shores of the Great Lakes to the frontiers of Pennsylvania, New

York state, and New England, with key locations marked out, along with paths connecting one location

to the next. The colour pallet is muted but nonetheless quite attractive;

highlights the action rather than smothering it. The board also features a Year-track

(1757-59), and turn-track (11 turns with a possible 12th on a

successful die roll for a late winter), and points tracks for each side (running

0-12).

F&IW is a block game, which isn’t everyone’s

cup of tea. If you’ve read this far, you’re probably a fan or at least curious.

The blocks in F&IW are of a typical size for a block game (comparable to

the Columbia Games’ block games or the Cavalry blocks used in GMT’s Commands

& Colors family of games) The British blocks are in a red very close to the

British Redcoat uniform crimson; the French blocks are in a rather pale blue (which

is historically more fitting than the expected royal blue). Two sets of

stickers are provided with the game; these are applied to one side of the

blocks, and represent the three types of units available to the players (French

unit stickers on the blue blocks, British on the red). The differences in the

sets are purely ascetic. I went with the more conventional of the two sets.

Also included are a handful of small black

cubes intended for track markers. There are several more then are needed on the

board, so we placed an extra one or two (as appropriate) on the 0-box to mark

when the twelve-point track had been lapped (i.e. a 0 block and a 3 equals 15 points,

two 0 blocks and a 2 would equal 26 points). We also used a spare block as a mnemonic

for the location of a battle, as the pieces are all removed to a battle board

for combat.

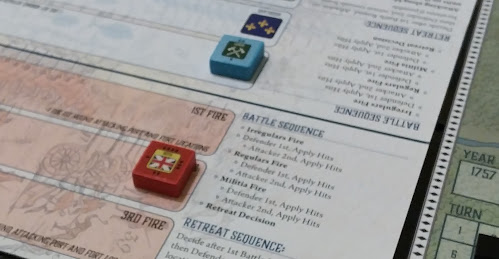

The Battle Board is where conflicts are

resolved. This is a thick 11” by 8½” panel with a combat ranks and instructions

printed on one side. On the reverse side is a break-down of the historical set-up

for the game.

The game comes with six custom dice, used in

the combat rounds. Units hit on their own symbols, of which there is only one

face on each die; Regular army units hit on their respective flags, Irregulars

hit on crossed tomahawks, and Militia on a roll of crossed muskets. The game also

comes with a single regularly-pipped six-sider, for rolling at the end of the game-year

to see if a late winter allows an extra turn that year.

French and Indian War comes with two copies of the rule book; this is something Worthington started doing a few years ago, and it is such a boon. The rules run to eleven of the twelve pages, and these include solitaire play guidelines and the option for hidden simultaneous movement (the game also comes with a pad especially for recording your movements before the simultaneous placement), which I can’t speak to because we haven’t tried that, but now I’m really wishing we had for at least one game; when we get around to playing this again I'll make sure to use the hidden movement rules and report back. The last page has a map with abbreviations for the hidden movement mode, but it doubles as a player’s aid (a good thing there’s two copies of the rules).

Play

The forces in French and Indian War are

comprised of regiments Regular (professional) soldiers, cohorts of Militia,

bands of Irregular units (Indians and Rangers), and naval units for gaining or

challenging control over the Atlantic. These units are represented by labelled

blocks, Red for the British and their allies, light blue for the French and

their Indian tribes allied to Louis. The strength of each unit is indicated by

a decreasing number of pips on the sides of the edges of the block sticker; as

is typical with most block games, when a unit takes damage, the block is rotated

counter-clockwise so that the upper edge always represents the current strength

of the unit (i.e., a four-pip regular unit takes a hit; it is rotated so the

upper edge now shows three pips). Combat rounds go rank by rank; first

Irregulars, then Regular troops, then Militia. Defenders roll first, and hits

are taken immediately, so there’s always the possibility of disadvantage as the

attacker, especially when attacking a fort or a port settlement (attacking Irregulars

and Militia roll with one les die on their first round).

The game is

divided up into three years of 11 or 12 turns to a year, depending on the roll

of a six-sided die to determine whether Winter sets in early or late (on a roll

of 4-6, the players get one more turn for the year; on a 1-3 the snow comes

early). Each location has a victory point score, which also corresponds to how

many units can winter in that location. A winter garrison can exceed the VP

number by one irregular unit and take no penalty, but any further units will

take a one-pip drop in their strength (reflecting desertions, Militia members returning

to their homesteads, etc.). Getting caught with a larger formation in a

small town can be devastating.

The play action of French & Indian War is

deceptively simple; with each turn, each side – beginning with the British –

may move a unit of units from one location. These units can move from their point

of origin to a single location, or they may disperse to separate adjoining

locations, but most can only move to an adjacent location. The exception to

this is the Irregulars – the allied Indian tribes and local Ranger units – who can

move to a second connected location.

When you arrive at a location already inhabited by the enemy, you fight. The number of pips across the units in a rank dictate how many dice you roll for that rank, and you hit on that ranks’ symbol (crossed hatchets for the Irregulars, crossed muskets for the Militia, and the Union Jack and Fleurs de Lys for the British and French Regulars respectively). In this game the dice are unforgiving. Whatever you are fighting with has a one-in-six chance of raining hurt down upon the opposing side. Sometimes a whole round or two of combat will prove ineffectual for both sides. But occasionally a single roll can be devastating. Only occasionally, though (statistics say so). Being a block game, you don’t know what your opponent has placed where until you test it, and in this, combat can have as much use as a method of probing for intelligence as its more obvious purpose. Knowing where the other side is strongest can deliver vital information regarding your opponent’s intentions.

For all the reduced movement options and

sometimes sluggish combat resolution, French and Indian War is a remarkably

fast-playing game. Our first run at it had all the usual qualities of a learning

game, and so ran to about two hours and twenty minutes, but from the third game

on, we managed to keep play within the 90 minutes suggested on the box. French

and Indian War is a tight game that flows easily, so long as you’re not given

to labouring over every difficult choice.

Appraisal

F&IW involves a combination of strategy,

guesswork and, to a degree, dumb luck, though not as much as it might appear on

the face of it. To win, one side must gain a clear ten-point majority in points

at the end of a year, after any territorial gains have been tabulated. Each

unit destroyed offers the victor a single point, but you’re not going to win by

killing the enemy. Taking territory is where the points are, but it’s not

enough to push the enemy out of his homes; to claim a location as a prize, one

of your units must reside there at the close of the year. That means, to have a

chance at winning that ten-point lead, you will have to spread your forces fairly

thinly in an effort to gain those extra victory points. And if you don’t win

the game that year, you’ll be spending turns gathering up your units for

another fight or two before trying to claim all that territory again. This also

means that a fight to the death isn’t in your interests. If you knock out two

of the other guy’s units but lose one or two yourself, you may not be able to

cover the terrain you need for those elusive points. French and Indian War is a

long string of difficult choices.

While it is a relatively simple game

to learn, and only really has one scenario (two if you count the historical

set-up and free placement as separate scenarios), French and Indian War is a

rare gem of a game; I found it reveals its depths slowly, rewarding multiple

games with new insights. It elegantly captures the difficulties of waging a

frontier war with restricted movement options, limited resources and manpower, and

a mutual enemy in the harsh North American winters I’d put it on the same level

as the best of Columbia Games' block games. I think the key to approaching the game is to

adopt a guerrilla mindset, more Mao Zedong than Antoine-Henri Jomini. It was impossible

to run a set-piece decisive battle in the vast wilderness the Great Lakes

region in the mid-eighteenth century. Most actions in the game are small concerns,

with one side conceding the ground and backing off to maintain their force

strength of another day. Sometimes it can feel like whack-a-mole; each side is

limited in its resources and stifled in its manoeuvre options, and I can see

how some might find the frustration insurmountable, but its these elements that

make the game such a strategic showpiece. It’s difficult to spring a surprise

on your opponent when it takes your forces three turns to get into a position

to pounce. This game rewards a flexible approach to fighting, and makes unanticipated

demands on its players.

I’m sure some folks will balk at the

ponderous nature of F&IW; the limited movement, the potential for

successive rounds of ineffectual combat, and the requirements of winter-quartering

potentially chewing up your last three or four moves for the year. But all

these aspects work together to abstractly recreate the difficulties of fighting

a war in the truly untamed and inhospitable environment of the Great Lakes

region. Dealing with these restrictions through the course of play elevates

this game of simple mechanisms into a deep historical simulation. French and

Indian War is a deft and elegant example of game design.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment